|

|

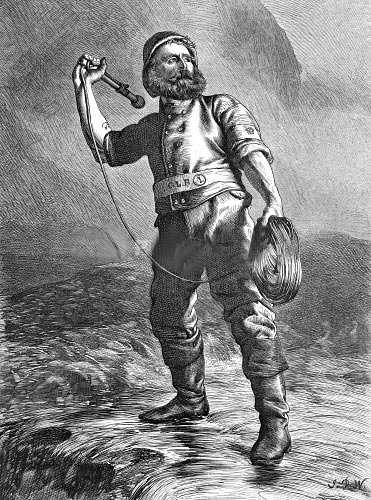

Through the cruel fog and blinding mist ill-starred vessel -come from no one knows what port, and bound no one knows what port, and bound no one knows whither - (though on the pier and the high sea-terrace there are shuddering guesses and whispered suppositions)-is driving with spread fragments of sails and shattered spars, like a blind, mad despairing, hunted creature, upon the Northumbrian cliffs. It is rushing eagerly on its death. One mast has gone by the board, and the other will soon follow. Its deck is swept by every wave; death stares in the face the few frightened shouting men. If help does not come before nightfall the sea must have them all in a few hours. The whole population of Cullercoats are out on the shore watching that ghastly sight. The women are screaming, the frightened children are clinging to their mothers’ sides. The sympathy felt is such as only those can feel who have fathers and husbands and lovers away at sea, and liable to the same danger. Many of those staring now so wildly seaward have lost sons and husbands and brothers off the same off other coasts. Through the cruel fog and blinding mist ill-starred vessel -come from no one knows what port, and bound no one knows what port, and bound no one knows whither - (though on the pier and the high sea-terrace there are shuddering guesses and whispered suppositions)-is driving with spread fragments of sails and shattered spars, like a blind, mad despairing, hunted creature, upon the Northumbrian cliffs. It is rushing eagerly on its death. One mast has gone by the board, and the other will soon follow. Its deck is swept by every wave; death stares in the face the few frightened shouting men. If help does not come before nightfall the sea must have them all in a few hours. The whole population of Cullercoats are out on the shore watching that ghastly sight. The women are screaming, the frightened children are clinging to their mothers’ sides. The sympathy felt is such as only those can feel who have fathers and husbands and lovers away at sea, and liable to the same danger. Many of those staring now so wildly seaward have lost sons and husbands and brothers off the same off other coasts. The brave hardy Northumberland fellows are ready to risk their lives. With cheering shouts they drag down lifeboat, but it cannot live in such a sea; twice it capsizes, and the men are saved with difficulty; it will not breast those mountains of breakers, and at last it is dragged back in despair; the doomed men out yonder groan in anguish, and one of them hopelessly flinging himself into the ghastly "hell of waters" instantly perishes. Then, as it grows darker and hope diminishes, rockets are fired, but the wind is too strong for them. There is but one resource left, and that all the old Tynemouth pilots and fishermen gathered there with the raging wind and spray on their rugged faces know but too well,- that resource is the Heaving Stick. If that does not carry a line to the ship the wreck must break up in half an hour. This heaving stick is a piece of bamboo, about eighteen inches long, with a ball of lead at one end, which makes it look like a deadly weapon- a life-preserver or death-giver from some dangerous foreign country. At the other end of the bamboo is a stout leathern loop, like that of a hunting-whip, to which the line is attached. There is one man here famous for the use of this, and that is Joseph Robinson, the first Captain, as the initials on his belt show, of the Cullercoats Volunteer Life Brigade; he can swing the stick seventy-five yards and even further still when his blood is up and there are drowning fellow creatures to save. Robinson is a fisherman, a Tyne pilot, and the more danger he is in, the more cool, prompt, and daring he becomes. The crowd make way for him as, with sou’-wester pushed back, coil of light rope in one hand and the heaver in the other, he comes to the front. His arms are free; he is booted and belted for action. What a sturdy, manly Englishman he looks as his quick eyes take in at a glance the exact position of things-the shattering vessel, and the men clinging to the one spot of safety where the waves do not make a clean breach. You can see them now, for the wreck is nearer, beating on that out lying spit of rock, which pierces the timbers like the tusk of a sword-fish every moment; the sailor poises the stick, you see the corded muscles of his brown arms swell with repressed energy. If that brave man misses this throw, or if the cord lodge in some top hamper of rigging out of reach of the wretched men, open-mouthed death has them now at one fell leap. Pitying angels, guide in the very jaws of destruction! The men round the Captain move to give him free room. The screams of the wrecked sailors can scarcely be heard now, what with the roaring wind and the surging sea. Every moment shattered planks come drifting in, with now and then a corpse bound to some split spar. Alone, against all these raging forces of destruction, stands up the Cullercoats Captain-keen-eyed, resolute, and imperturbable. Watching a moment when the wreck lifts upon wave, and beats closer upon the rock, he hurls the stick with tremendous force and accuracy. Will it reach? The fisherman, blinded by the spray, can hardly see for a moment where it has fallen. Yes, yes! God be thanked, it has fallen like a lasso, and lapped round the mast! A rejoicing shout rises from the Cullercoats men. In a moment a boy, cat-like, has reached it and secured it to the wreck. In a minute or two more, along the tightened rope the half-drowned men reach the shore. The Volunteer Life Brigade has saved more lives. To-morrow morning, when the winter sunshine shall rest peacefully on the red roofs of Cullercoats, there will be no signs of the doomed vessel from whence the men were saved, and the sea will bask in the cold light, as innocent and calm as if no grave lay beneath its treacherous surface. The Heaving Stick can only be thrown in the manner shown in the engraving about forty yards. In a wreck at Tynemouth a fortnight ago the crew was saved by a rope thrown in this manner. When in very dangerous positions Robinson has a rope attached to his belt, and this rope is held by his companions. [from: The Graphic, Feb 19th 1870, engraving of a picture by J.D. Watson] "The Christmas number of the Graphic for 1871 contained an extra sheet, the engraving of a picture by J.D. Watson, entitled 'Saved' - a picture representing a Cullercoats brigadesman, Joe Robinson, standing on the rocks receiving a woman and child who had been brought to shore from wreck by means of the running gear." p105, 'Historical Notes on Cullercoats Whitley and Monkseaton'. W.W. Tomlinson, 1893. |